It rained on the ceremony to officially open the Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds courts at Murray Park in Long Island City. Nature challenged us to play and work within its system. Early in the day, the rain was a disappointment as the forecast canceled a youth camp run by Dominic Tiger-Corteshe of H.O.O.P. Medicine. It moved the MoMA PS1 and Common Practice programming, including the art-making workshop, to MoMA PS1. It scaled back the opening ceremony to a land acknowledgment prayer by Tecumseh Ceaser accompanied by dance and song by members of the Shinnecock tribe. But, there was a lesson about water hovering just beyond my awareness, and the more I spoke with Edgar Heap of Birds that day, the more I understood its significance.

Edgar Heap of Birds is an agent of memory. The practice of reminding is inherent to his work, which predominantly addresses the atrocities suffered by native tribes during the establishment of the United States, as well as the ongoing violence against natives. There is a balance of confrontation and quietude in his art. His multi-disciplinary forms include monoprints on rag paper with slogans like “WE SEEK THE ORIGIN OF THE WORLD”, sign installations in the Native Hosts series that read “KROY WEN TODAY YOUR HOST IS SHINNECOCK”, and the Neuf series of acrylic interpretative landscapes. When I interviewed him at MoMA PS1 about the Neuf paintings becoming two mural basketball courts in Long Island City, he was quick to note the proximity of the East River and the Atlantic Ocean. Two bodies of water that are often out of sight and out of mind in this sprawling metropolis with towering buildings that obstruct the horizon lines.

“New Yorkers don’t think about the ocean,” he said, and stressed the importance of remaining aware of the presence of bodies of water. “When the hurricane comes you’ll remember the ocean when it floods your subways.”

That morning the rain was part of a diminishing weather system that produced Hurricane Ian and decimated the western coast of Florida. It was a reminder of the power and magnitude of water. In contrast, the Neuf series presents tranquility in the lands and water; an ecosystem at peace. For Edgar Heap of Birds, “the paintings give us that perspective of the beauty of water and that you have to be aware of it.“

There is movement to the paintings. His brush strokes invoke speed, even if the full scope of the canvas suggests serenity. It’s a fitting surface to a basketball court where speed and fluidity of movement are on display. And yet, for all the quickness of a pick-up game, it can look like a choreographed dance from afar. It’s one of the ways in which Edgar Heap of Birds sees basketball as art. He’s been a lifelong player and lover of the game. He’s played pickup during his academic pursuit of the arts in Berkeley, Oakland and Philadelphia. He was at Temple University in the 1970s, attending Sixers games at the Spectrum to watch Julius Erving and Daryl Dawkins battle Kareem Abdul Jabbar. And now, as a season ticket holder for the Oklahoma City Thunder he will find himself at the Joyce Theater in New York City thinking about how the modern dancers are not much different than watching Russell Westbrook in his prime sky through the lane for an acrobatic layup.

“You can see the world’s best dancer at the Joyce and the world’s best basketball players and see that it’s a dance,” he said. “It’s spontaneous invention when you’re going to the hoop or just playing the game. It’s just an interpretative expression that goes beyond sport.”

Basketball and dance intertwined at the opening event presented by Common Practice for Murray Park. The rain ceased and the attendees joined in a dance to celebrate the land, which according to studies, was once a nexus of Rockaway, Wappinger, and Matinecock tribes. Led by Tecumseh Caesar and members of the Shinnecock tribe, we spread tobacco at the foot of trees in the park to thank mother earth and the Shinnecock dancers led everyone in a round dance. Following the acknowledgement ceremony, attendees were invited to play knockout with the team from Project Backboard. In those games of knockout you could feel the ebb and flow of fluidity and chaos. A series of made buckets created a flow, but a few back-to-back arrant misses produced a scramble to survive.

Edgar Heap of Birds knew about the proximity to the East River when he was approached by Project Backboard to collaborate. He views the surroundings as a “beautiful synchronicity” for his mural courts. He said his Neuf paintings were all done near an ocean. He would be in the Caribbean or Hawaii or Mexico, looking out onto the waters and the brush strokes of acrylic would produce terrains in muted yellows, red clay, and all the shades of blue. Neuf means four in Cheyenne. The holy number carries a multitude of meanings and uses within the tribe. For example there are 44 chiefs. Also, that day at MoMa PS1, Edgar Heap of Birds’ custom Oklahoma City Thunder jersey was the multiple number 16. 4 x 4=16. There are 16 points on the secondary inter-cardinal directions compass. But for the paintings, he was specifically thinking about the four seasonal shifts of solstices and equinoxes.

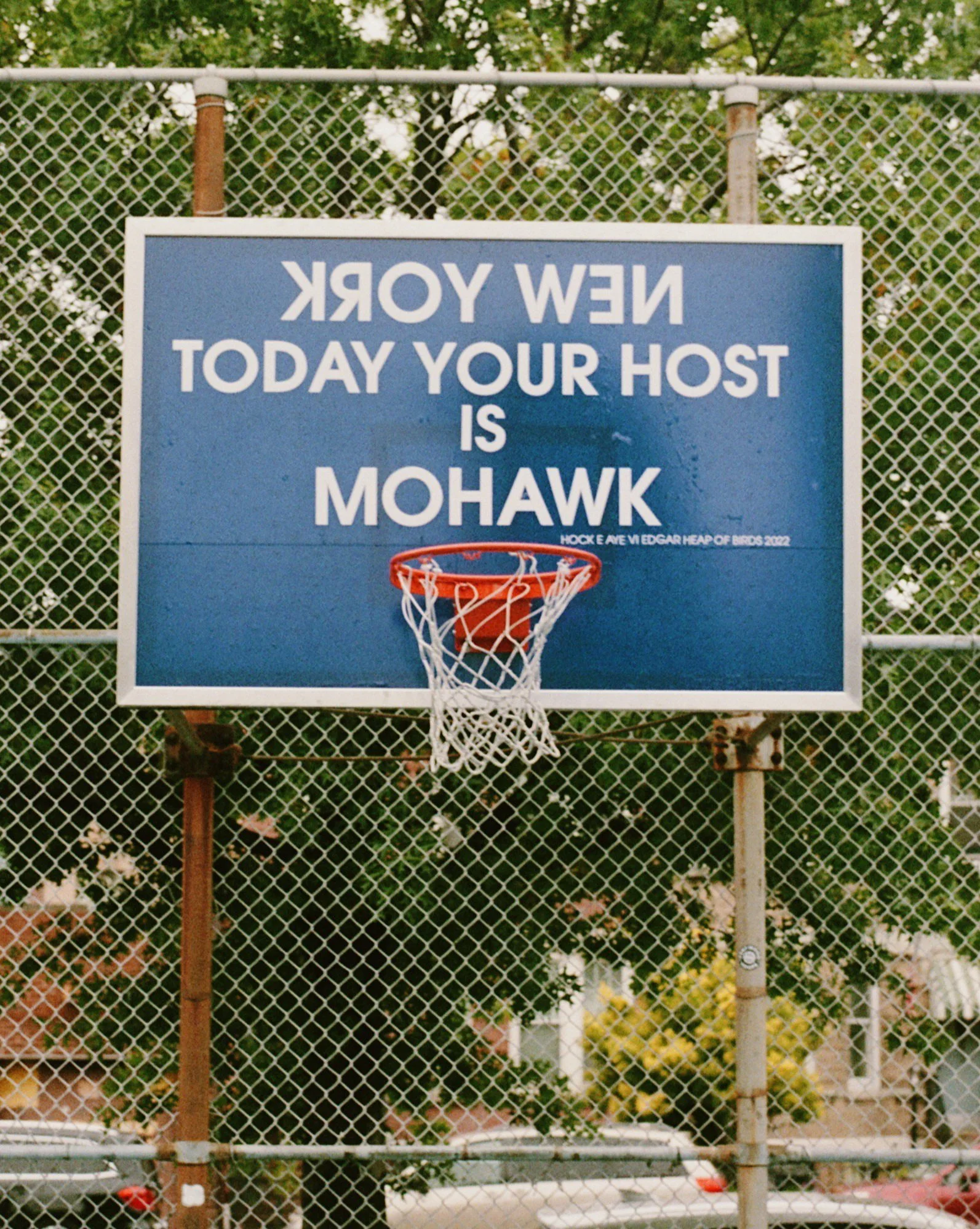

There are two courts with four backboards at Murray Park. Each backboard is fitted with a decal from the Native Hosts series. The white lettering announces four tribes of Long Island who act as hosts of the court, as well as hosts of New York City. Again, a reminder. A request for sovereignty. A continuation of Edgar Heap of Birds’ pursuit to erode and puncture systems of oppression. And even with the Native Hosts signs’ placement on the backboards—dubious in their impermanence—it feels like the request for acknowledgement remains conditionally accepted. For Edgar Heap of Birds these battles have been a part of his artistic life.

In 1988, Edgar Heap of Birds faced censorship by the mayor of New York City, Ed Koch. For those who’ve seen the graffiti documentary Style Wars, Koch was adamant in his criminalization and scrubbing of the graffiti movement across the five boroughs. Four years after the release of the documentary, the mayor’s office censored a display of Native Hosts, a sign series addressing the formation of cities and monuments over native land, by only displaying six of the 12 intended signs. Each sign was intended as a humble honoring of the 12 tribes whose land was seized by white settlers throughout Long Island. The censorship happened despite the installation being commissioned by the Public Arts Fund and no other works receiving partial display.

The mural court is not a temporary installation and is fully permitted by the New York City Parks Department. However, NYC Parks has restrictions when it comes to the construction of basketball goals. The display of artwork on the backboards is forbidden. Once again, the Native Hosts signs have been censored. For Edgar Heap of Birds the awareness of these battles remains part of a lifelong process cooked into the work.

“It’s been 30 years now [since the Koch censorship],” he said. “It’s not an overnight success. We battled all the time. I still battle in some cases to be heard.”

The argument against Koch’s criminalization of graffiti was that there was a burgeoning collective of New York artists who simply had no place to paint and no resources. Their expression was built from inventing a space where their work could be seen, no matter the consequences. Henry Miller once mused in his book The Air-Conditioned Nightmare that a person can “ride for thousands of miles and be utterly unaware of the existence of the world of art. You will learn all about beer, condensed milk, rubber goods, canned food, inflated mattresses, etc., but you will never see or hear anything concerning the masterpieces of art.” The work of Project Backboard to bring museum-level art to public spaces, which recently includes the works of Faith Ringgold, Felrath Hines, and Edgar Heap of Birds, aims to be part of the solution to that American condition. The art courts will always primarily be a place of play, but they also fundamentally provide a visual future for the invention of new surfaces for public art.

“Of course all good and productive public art is often created for a community,” Edgar Heap of Birds said. “These citizens can use the work, add to it and/or be enlightened. Effective public art is not to only ‘decorate.’ The community adds to the work by playing/being active on the court paintings.”

The Neuf courts at Murray Park are open for the community and open to interpretation. I like to think that the ceremony and land acknowledgement established the sovereignty of the courts. These are now self-governing spaces. What I hope is never lost is the awareness of water. Even if it’s subtle, and merely understood as a blueish surface that feels as though you're playing on water, I hope it remains a reminder. There’s deeper meaning for those who seek it. The impact of water on our lives is perhaps one of the most significant relationships we have with nature.

“Our courts speak from a Sovereign perspective, in that to honor the earth, seas, animals, sky, natural world is a Native focus and priority,” he said. “Sovereignty is about origins and honor to offer the good as well as protect what we hold sacred, such as our youth and elders, those entities should always come first along with our natural world.”

On October 29, Common Practice and Project Backboard will be hosting an open run from 12pm to 4pm at Murray Park that will feature the reinstallation of the Native Hosts backboards. The open runs on both courts are for all ages, anyone and everyone who’s trying to hoop. The event is in partnership with 5-Star Basketball, Kindred Studios, H.O.O.P. Medicine and MoMA PS1. Come get a bucket.