The pandemic placed a higher premium on public spaces. As shelter-in-place guidelines eased, people returned to outdoor basketball courts with a newfound awareness and appreciation for these public courts. And if a park had no place to hoop, it raised questions. Whereas Hoops was asking those questions in St. Louis and directing that concern towards 1,300 acres of urban public park.

Forest Park in St. Louis is the “Crown Jewel” of the city. But visual artist John Early and sports studies scholar Noah Cohan noticed that basketball was missing from the extensive amenities of the park. Forest Park has tennis courts. Forest Park has volleyball. It has baseball and softball. Its waters are used for kayaking. Forest Park even has cricket and archery. People are permitted to shoot arrows at Forest Park. But as Whereas Hoops notes, “Basketball would apparently just be too much, and too dangerous.”

“There was certainly the sense that basketball would mar the pristine image of a park that so many for so long have worked hard to cultivate and maintain,” Early and Cohan wrote in an email interview.

For the book, the two used the legalese of “whereas” which is short hand for “because the following things are true, I proclaim that something should happen.” They asked: How can one of America’s most popular athletic pastimes be absent from St. Louis’s signature public recreation space?

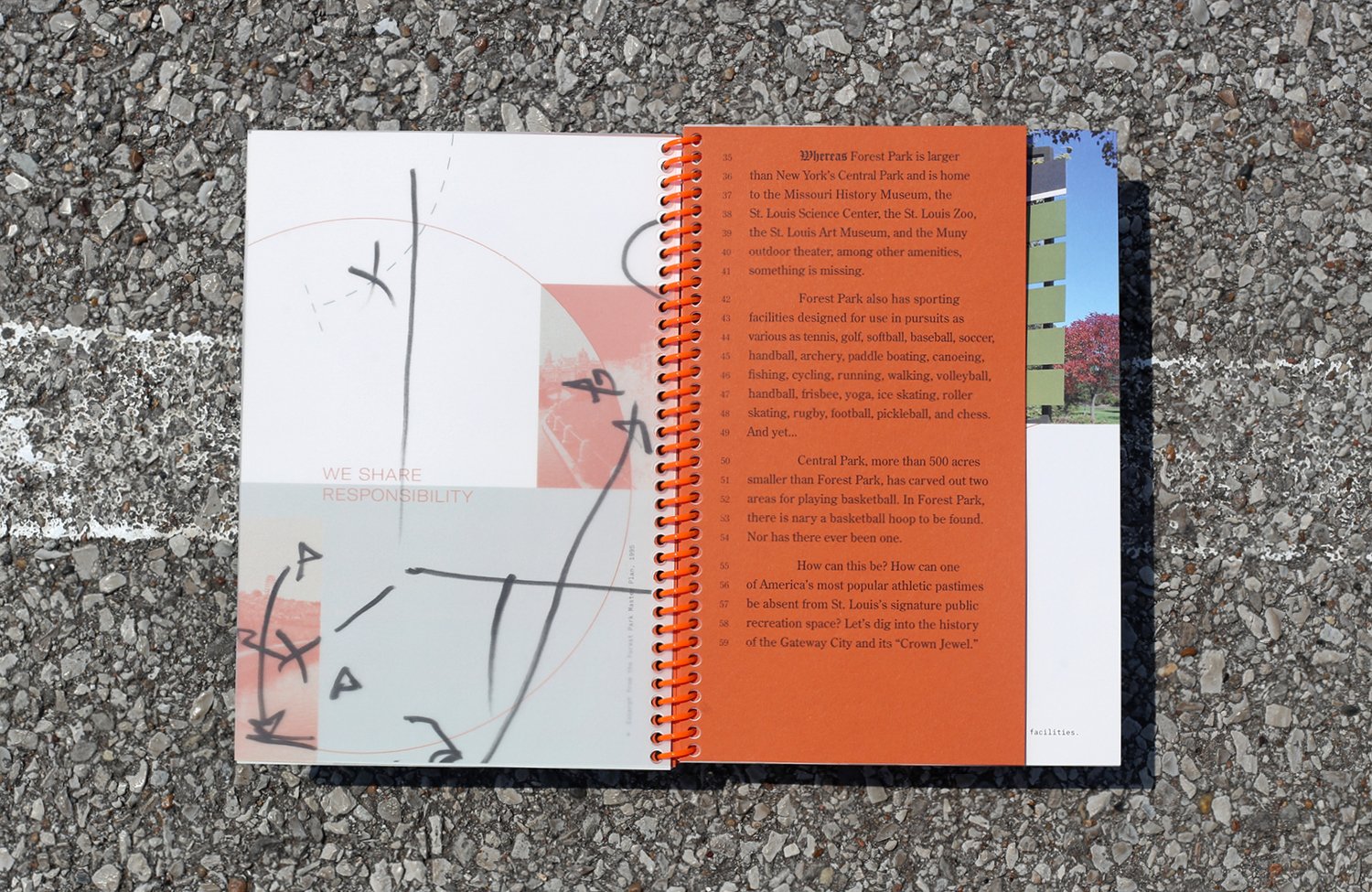

Unsurprisingly, the research led to rare instances of the game infiltrating the park and the structural racism that repeatedly sabotaged attempts to bring basketball to Forest Park. They presented their findings in a spiral-bound book that fuses scholarship, artistry, and activism. The limited pressing of 100 was distributed to St. Louis city officials and civic leaders, with the remaining 25 distributed in a raffle that gave preferences to libraries, special collections and other educational contexts. Books were distributed free of charge thanks to the generous financial support of the Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity & Equity at Washington University. Quite purposefully, Early and Cohan make a strong case for basketball in Forest Park and as the book went to print, it looks as though the change is imminent.

The following is an interview with John Early and Noah Cohan of Whereas Hoops.

Let's start with the catalyst. Was there one moment or a series of events that inspired the two of you to explore this story?

The genesis of the project was five years ago at a conference called “The Material World of Modern Segregation” held here in St. Louis. The two of us were each presenting separately on different ways in which racism is present in the sporting landscape of St. Louis, sometimes explicitly, other times implicitly. Over drinks, we discovered our shared NBA fandom. As non-native St. Louisans, we also agreed that it was quite evident and extremely odd that outdoor basketball courts were absent from St. Louis’ “crown jewel,” Forest Park. The much celebrated park hosted the 1904 World’s Fair and stretches a massive 1,300 acres across the city. St. Louisans are quick to point out that it’s 1.5 times the size of Central Park, however it has no basketball courts.

We thought it would be productive to collaborate on some research about basketball in relation to the park, but nothing concretized until the country began going into COVID lockdown in early 2020. Each of us had the benefit of a stable job, so with a bit of idle time we began the project in earnest with a simple Instagram post. Early posts focused on the surprisingly rich basketball history of St. Louis. We then shifted to posting about Forest Park, specifically the history of the park, its contested uses over time, and its rise to become the “No. 1 city park in the United States” according to the most recent USA Today Readers’ Choice Awards.

When did the project begin to shift from collaborative research to hybrid activism?

The project was intended from the outset to be public facing and live outside an academic journal or art gallery. We had a vague idea of what forms it might take given our respective fields of study and practice, but we were comfortable with letting the research and the process both play out organically. The stakes of posting our research on Instagram were low, so that was a helpful way to begin. Could the project possibly not gain any traction and just fall flat? Absolutely. But we believed the questions we were asking were important ones to be posing and drawing attention to.

Whereas Hoops digs deep into the park history and the rare instances of basketball infiltrating its grounds. How far back did you have to go to find basketball in Forest Park?

What we discovered, in fact, is that basketball had not once been played in Forest Park, whose founding in 1876 predates the invention of basketball by 15 years. We searched high and low for evidence to the contrary–searching newspaper and photographic archives, speaking with sports historians, and looking at old maps of the park–but found none.

There were a number of instances of basketball being played adjacent to the Forest Park, however, most notably the 1904 Olympic Games hosted across the street at Washington University in St. Louis. Basketball was an exhibition sport at those games. More interestingly there was a young women’s basketball team from the Fort Shaw Indian School in Montana who came to St. Louis that summer and played a series of exhibition games near the park as part of the World’s Fair. They soundly defeated all opponents and were given a trophy declaring them “champions of the world.” Granted, basketball in this context was being used as a tool to assimilate Native Americans into American culture–”kill the Indian, and save the man”–but the fact that a team of non-white women excelled at the sport powerfully testified that basketball was not the exclusive domain of neither whites nor men.

As the book explores recent instances in which city officials have introduced the inclusion of basketball, it mysteriously dies in committee. Did you approach past and sitting officials, like Alderman Joseph Vaccaro, for commentary or insight? Or perhaps former Alderman Antonio French?

We did not speak directly with either of those two aldermen–one did not respond to our request to talk–but there were plenty of newspaper articles and media reports about their two separate board bills calling for the construction of basketball courts in Forest Park. All the coverage focused on questions of crime and safety relative to pick-up basketball. “Stretching police resources” and “bringing groups to the park that would cause problems” were among the reasons for opposition, not to mention some saying that courts would take away precious green space in the park. No matter that the park boasts courts, fields, and recreational spaces for a dizzying array of sports and activities as varied as baseball, softball, tennis, soccer, handball, archery, cricket, coneing, kayaking, fishing, cycling, jogging, volleyball, ice skating, rugby, chess, pickleball, and Irish hurling. Basketball would apparently just be too much, and too dangerous. There was certainly the sense that basketball would mar the pristine image of a park that so many for so long have worked hard to cultivate and maintain.

It's interesting that Forest Park is co-managed through the City of St. Louis and a private conservatory non-profit. Can you elaborate on that relationship and how it impacts the park?

In short, Forest Park would be nothing like it is today apart from the financial backing of Forest Park Forever, a private nonprofit conservancy founded in 1986 that works in partnership with the parks department to “restore, maintain and sustain Forest Park, as one of America’s great urban public parks for a diverse community of visitors to enjoy, now and forever.” After the World’s Fair, Forest Park gradually fell into disrepair. The city simply didn’t have the money for regular park upkeep and maintenance. Wanting to restore the park–and, by extension, the city– to its turn-of-the-century glory, a group of the most wealthy St. Louisan founded Forest Park Forever. By our estimates, the organization has raised over $200 million for the park since its founding. The City of St. Louis has over 100 other public parks, many of which still suffer from neglect. Apparently only Forest Park is forever.

The two of you did an experiment alongside this project. You fashioned a hoop to your car and took it to the park to see how the community might respond to basketball’s presence. What did you learn?

We figured the best way to get hoops into the park–at least in the short term–was to bring them there ourselves. So, John welded a trailer hitch that would fit onto his minivan, found an old basketball hoop and backboard, and fashioned a basketball pole that could disassemble for easy transport. We believe that June 5, 2021–the day we first brought our hoop to Forest Park–was the first time basketball had ever been played in the park. We set up in a centralized location in the visitor’s center parking lot and had a great time.

We brought the hoop into the park several more times that summer and fall and have just recently begun to bring it out again now that the weather is nicer. We always invite friends and supporters of the project to join us, but most enjoyable are the passers-by who give us a thumbs up, snap a quick picture, or stop and shoot for a few minutes. Parents and kids are the best. We can lower the hoop to six feet, which makes it fun for even the smallest child to play. Just last weekend we had a wedding party stop by the mobile hoop, with the bride and groom each shooting from long range. The gatherings are all about community and joy. Of course, bringing the hoop into the park is about raising awareness as well, but at the end of the day an outing is only successful if we see smiles on faces, have a few good conversations, and make some new friends.

The book concludes with good news. As of February 2022 the Advisory Board is moving forward with a planning process to install courts. Have there been any updates since this book went to print?

Yes, the Forest Park Advisory Board is currently engaged in the long, bureaucratic process of considering whether to install basketball courts in the park. Interestingly, the process began around the time Whereas Hoops was getting off the ground in early 2020. Regardless of whether the relationship between their effort and ours is causal or correlative, we’re excited these developments are happening and have been an active presence at each and every advisory board meeting where basketball has been discussed. Our goal in attending these meetings is to help keep the ball moving forward and ensure the basketball courts–should they be built–are constructed in the most equitable, functional, and aesthetically pleasing manner possible. Currently the advisory board is somewhere between steps 4-6 in the 9-step project approval process. The preliminary project has been approved–including the selection of a site–and they’re now in the process of creating, reviewing, and approving the preliminary design. There was time for public input at the end of step 3 and there will be again at the conclusion of steps 6 and 9.

The release of the book is limited and you made an effort to see to it that copies went to libraries. How did that process go?

From the beginning, our intent with the artist’s book was to create a publication that could make the project accessible to a wide audience. Initially we intended to do this through making a zine, but during our initial conversations with graphic designer Becca Leffel Koren–who did a marvelous job designing the book–the three of us agreed that for the publication to have the greatest impact as an object, we’d prioritize using varied paper stocks and sheet lengths. We felt it was important to raise the level of the book by better aligning its form with its rich and layered content. This meant we were limited to an edition of 100, but we’ve had more than enough to distribute to city officials and civic leaders, as well as donating them to special collections and libraries both locally and regionally. We’re currently in conversation with a number of librarians and curators and are quite excited about the possibilities of having the book available to a range of audiences.

This book addresses the problems of structural and environmental racism with the park’s natural amenities functioning as a Trojan Horse for the racially-motivated omission of basketball. These forms of oppression are covert, which can make them more difficult to research and prove. What advice would you offer to activists or communities who may not know where to begin when it comes to uncovering structural racism?

This answer may be a bit on the abstract side, but we believe developing an ethic of active observation is essential to effecting any kind of meaningful change in our communities. Part of what that means is critically looking, being curious, asking questions, and engaging with community members and stakeholders to learn from their experiences and perspectives. It’s a bottom-up approach that doesn’t superimpose categories of thought or immediately offer solutions. This ethic we’re proposing also speaks to the importance of being aware of one’s own positionality in an endeavor like this. One question we’ve been attentive to from the outset is how our jobs (as university professors) and our identities (as straight white males, each with a wife and kids) might impact our work, research, and advocacy both positively and negatively. On the positive side, we’re able to do things like set up a mobile hoop in a high traffic parking lot patrolled by park security officers. It’s disruptive for sure, but tolerated without issue. On the other hand, the two of us can’t speak firsthand about the experience of feeling unwelcome in the park or being an African American in St. Louis, so we began a podcast to foreground stories and voices from others in the community. The project has always been about helping move St. Louis toward being a more equitable, just, and flourishing city. It’s not about the two of us. We’re in a position to impact the community, however, so we feel it’s our responsibility to use that platform to push as far as we can.

Stay up on the developments of the courts in Forest Park as well as Whereas Hoops bringing their mobile hoop for free shoot arounds. Give a follow to @whereas_hoops